Introduction

Skeletal Class II malocclusion prevails in 15% of total malocclusions in Indian population.1 Prognathic maxilla, retragnathic mandible, or a combination of the two may be the cause of the skeletal class II malocclusion. The most frequent cause of skeletal class II malocclusion is mandibular retrognathism.2 Growth control, treatment for camouflage, and surgical correction are some of the several management strategies for skeletal class II malocclusion. In cases with mandibular retrognathism after growth completion, two treatment options can resort viz; camouflage orthodontic treatment and ortho-surgical management. Camouflage treatment accounts for dental correction achieved without addressing the skeletal problem. Despite being extremely invasive, surgical mandibular advancement can address skeletal imbalances.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 A combination treatment such as distraction osteogenesis, which exploits the benefits of both growth modulation and surgical corrective treatment can be a better option in the management of skeletal discrepancies post-growth cessation. Mandibular distraction osteogenesis along with bilateral sagittal split osteotomy 3, 4, 5 is commonly used for mandibular advancement.6, 7, 8 Surgical mandibular advancement of more than 7mm with a bilateral sagittal split osteotomy show increased chances of relapse postoperatively9, 10, 11 along with increased incidence of condylar resorption.12, 13, 14 Cases requiring more than 7mm of mandibular advancement are better managed using distraction osteogenesis since chances of postoperative relapse, condylar resorption, and damage to the inferior alveolar nerve are reduced owing to relatively slow soft tissue expansion allowing adequate hard and soft tissue remodelling.15, 16, 17, 18, 19 Distraction osteogenesis is a common treatment option and is more successful for non-syndromic growing patients between the ages of 11 and 17 years who have a skeletal Class II malocclusion and an average to low mandibular angle16, 8, 15,20, 21, 22, 23 This article demonstrates how distraction osteogenesis was used to successfully treat one such patient, improving both the appearance and functionality of the stomatognathic system.

Case Report

Case summary

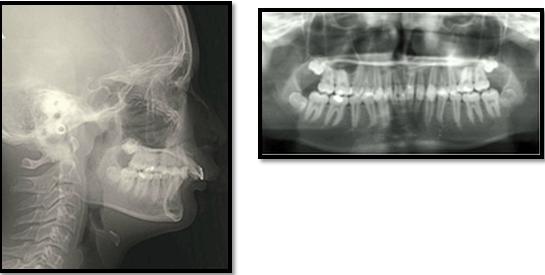

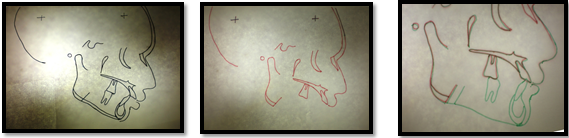

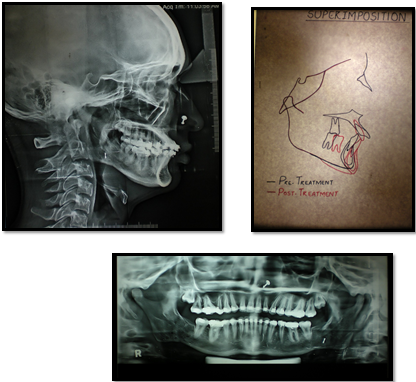

The patient was an 18-year-old female, and her main complaint was that her upper front teeth were positioned forward. Extra-oral examination revealed no signs of temporomandibular joint disorders. She featured a convex facial profile, a deep mentolabial sulcus, and a recessive chin. Intra-oral examination revealed patient in permanent dentition with dental caries wrt 12, 14, 22, 23 and 24, class II molar and canine relationship bilaterally with increased overjet, 100% deep bite (Figure 1). The radiographic study of the lateral cephalogram revealed a retrognathic mandible with an SNB angle of 72 degrees and an ANB angle of 7 degrees, resulting in a skeletal class II jaw relationship. The FMA of 20 degrees and Go-Gn to SN of 26 degrees are suggestive of decreased lower anterior facial height and horizontal growth pattern. The maxillary incisors were protruded with a U1-NA of 40 degrees and 8mm. The CVMI staging indicated that the mandibular growth spurt had ended (Figure 2 and Table 1). The patient's ABO discrepancy index was 23, which falls under the severe group (Table 2).

Table 1

Pre-treatment and post-treatment cephalometric measurements

Diagnosis

An adult female patient aged 18 years was diagnosed with skeletal class II malocclusion in CVMI-6 due to retrognathic mandible, convex profile, deep mentolabial sulcus, recessive chin, Angle class II division 1 malocclusion with class II canine relation, increased overjet, and 100% deep bite in conjunction with horizontal growth pattern.

Treatment Plan

The treatment plan was constituted as follows: — Restoration of caries teeth and prophylactic extraction of mandibular third molars. Fixed mechanotherapy for levelling and alignment of dental arches to be carried out with 0.022” MBT PEA. Distraction osteogenesis to lengthen the mandibular body to improve the mandibular retrognathisn and recessive chin to achieve class I skeletal bases. Optimization of overjet and overbite. Finishing and detailing with settling of buccal occlusion and retention.

Treatment Alternatives

An alternate treatment option for skeletal class II malocclusions with mandibular retrognathism after a growth spurt is camouflage orthodontic treatment employing extraction technique. Though, the skeletal issue is not fixed by this therapy. As a result, we chose surgical orthodontic treatment since it could accomplish the bulk of the patient's problem-list objectives. We chose mandibular distraction osteogenesis with bilateral sagittal split osteotomy above the other surgical options, since achieving class I skeletal bases required more than 7mm of mandibular advancement.

Treatment Progress

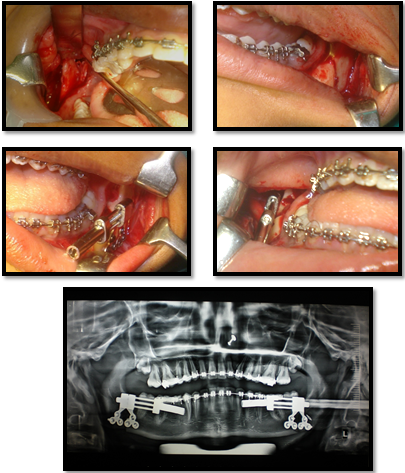

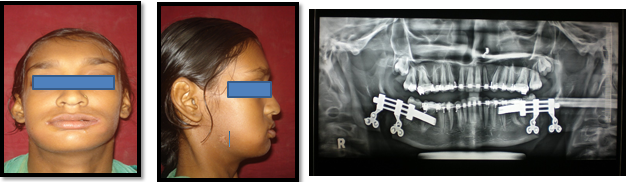

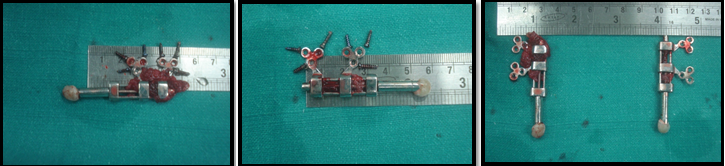

Restoration of caries teeth was carried out using light cure composite. Prophylactic removal of the mandibular third molars bilaterally was carried out. An MBT pre-adjusted edgewise appliance (0.022 x 0.025 inch) was placed in the maxillary and mandibular arches. Sequential archwires were placed starting from 0.016” NiTi, 0.016” x 0.022” NiTi, 0.017” x 0.025” NiTi, and 0.017” x 0.025” SS to achieve levelling and alignment of dental arches over a period of 06 months (Figure 3). Following levelling and alignment, pre-surgical radiographic analysis was carried out to assess the dental corrections achieved and detailed planning of the surgical procedure (Figure 4). Before the surgical procedure, 0.021” x 0.025” SS archwires were placed in both arches. The intra-oral distraction device (KLS Martin, Umkirch, Germany) was fastened to proximal and distal parts distal to the mandibular second molar bilaterally following a bilateral sagittal split osteotomy (at age 18 years 08 months) (Figure 5). The device was activated at a rate of 1 mm/day (0.5 mm per 12 hours) following an initial recovery period of 8 days. The schedule was continued for further 9 days till the patient exhibited anterior edge-to-edge relation (Figure 6). Post-distraction settling of occlusion was performed using box elastics to prevent post-operative relapse (Figure 7). Seven months after the desired activation, the distraction device was removed (Figure 8). Final settling of occlusion and finishing and detailing was carried out which took a further 3 months. A skeletal class I apical base relationship and an excellent facial profile with the ideal overjet and overbite were obtained after 15 months of ortho-surgical treatment (Figure 9, Figure 10). The patient was placed on retention using upper Hawleys retainers and lower FSW retainers and a regular follow-up was scheduled

Results

The patient displayed a decent facial profile, class I skeletal basis, and a tolerable occlusion at the conclusion of treatment. Improvements were made to the protruding upper lip, deep mentolabial sulcus, and inadequate chin. The overjet and overbite were optimized, and the dental arches were levelled and aligned (Figure 9). The post-treatment radiographic study of the lateral cephalogram revealed a balanced face with an FMA of 21 degrees and a Go-Gn to Sn of 28 degrees, as well as a skeletal class I apical base relationship with an ANB angle of 1 degree. The Co-Gn was raised by 8 mm, showing advancement of the mandible. The upper incisors underwent U1-SN retrusion with a 35-degree and 7-mm angle. (Table 1 and Figure 10 ).

Discussion

An 18-year-old patient with a skeletal class II malocclusion caused due to a retrognathic mandible with a receding chin had orthodontic therapy in conjunction with mandibular distraction osteogenesis. An 8 mm increase in mandibular length (Co-Gn) was seen in the present case. It was possible to acquire a decent facial profile when the skeletal imbalance was fixed. The patient's overjet and overbite were optimized after therapy, and the occlusion was satisfactory. Following bilateral sagittal split osteotomy for mandibular advancement, the literature search turns up numerous instances24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29 that demonstrate a change in stomatognathic function. Only a small number of papers, meanwhile, could be found that examined how individuals with skeletal class II malocclusions changed in terms of stomatognathic function following mandibular distraction osteogenesis.

Distraction following an osteotomy with slow incremental activation causes the separation of bony segments to cause the development of new bone, a process known as osteogenesis30. It was introduced by Codivilla at the beginning of the twentieth century and was popularized by Ilizarov through extensive studies describing the biomechanical principles of the technique that result in bone formation 31, 32. However, it was McCarthy who used this technique for the lengthening of hypoplastic mandibles.8 In contrast with the distraction of long bones, maxillofacial distraction involves the need to control three-dimensional movements with superadded complexity because of the shape of the maxillofacial bones, dynamic muscle activity, and involved dental relationship. This makes the technique less predictable than routine orthognathic procedures and requires meticulous planning for execution. Intra-oral distractors have the advantage of being less conspicuous as compared to extra-oral distractors. The callus formation and its remodeling in between the osteotomised segments and also distractor vector control are the two most critical aspects in obtaining the required skeletal and dental corrections.33 In the case of orthognathic surgery, the same degree of precision is difficult and might not be achieved as compared to distraction osteogenesis because of the slow traction and adequate adaptation time for the soft tissues which constitutes an increase in the soft tissue envelope (distraction histogenesis).34 Therefore, it was proposed that surgical growth modulation therapy, which combines orthodontic therapy with mandibular distraction osteogenesis, was effective in resolving skeletal disharmonies and enhancing facial features like the profile and function of the stomatognath and teeth.

Conclusion

Ortho-surgical treatment combined with mandibular distraction osteogenesis may be an efficient treatment option and can be considered as a surgical growth modulation therapy for correction of skeletal discrepancy in adult patients for improving facial aesthetics and stomatognathic function and therefore enhances the quality of life of the patient.